As a result of the JFK Assassination Records Collection Act, the Central Intelligence Agency ostensibly produced a copy of the Hart Report, more famously known as the “Monster Plot,” which was intended to be a definitive account of the Yuri Nosenko affair and a takedown of disgraced spymaster James Angleton. What the CIA actually released, however, resembles Hart’s actual report as much as the television edit of The Big Lebowski resembles the actual dialogue.

While they share a structure, narrative, and name, the report the Agency shared with Congress and the Federal Bureau of Investigation isn’t simply sanitized - it was outright rewritten to omit the more “dramatic” statements, such as the memo outlining a plan to kidnap and isolate Nosenko in a routine modeled after KGB prisons, the note suggesting faking a confession, or the list of possibilities that included his secret execution. When a Congressional committee investigating the assassination of President John F. Kennedy requested the report, CIA gave them the rewritten version despite it omitting all references to JFK and Nosenko’s claim of having handled Lee Harvey Oswald’s KGB file.

The Monster Plot, or less dramatically the Hart Report, chronicled the case of Nosenko and the long debate about whether he had been a bona fide defector, or a source of disinformation. This debate, and suspicions fueled by Anatoliy Golitsyn (another KGB defector), played a role in Angleton’s infamous hunt for moles in the Agency. Though Nosenko had previously contacted the Agency, he established contact again in the months after the Kennedy assassination. Nosenko said he was ready to defect, and that he had handled the KGB file for Oswald during his time in the Soviet Union. While the Agency was eager for any defectors and sources of information, Nosenko’s claims to be able to shine a light on Oswald and the Kennedy assassination made him irresistible.

However, a number of people within the Agency had their suspicions about Nosenko. These suspicions intensified when, amid probes into JFK’s death and questions about Soviet involvement, Nosenko appeared and claimed that the KGB hadn’t recruited Oswald or established contact with him. Regardless of whether the KGB played a role in the JFK assassination, it struck many as all too possible that Nosenko had been dispatched to quell suspicions about a Soviet role in the assassination. Others came to suspect that Nosenko was also being used to cover-up other KGB activities and to discredit other defectors. He spent several years in isolation and at the center of a debate that ultimately ignored his human rights.

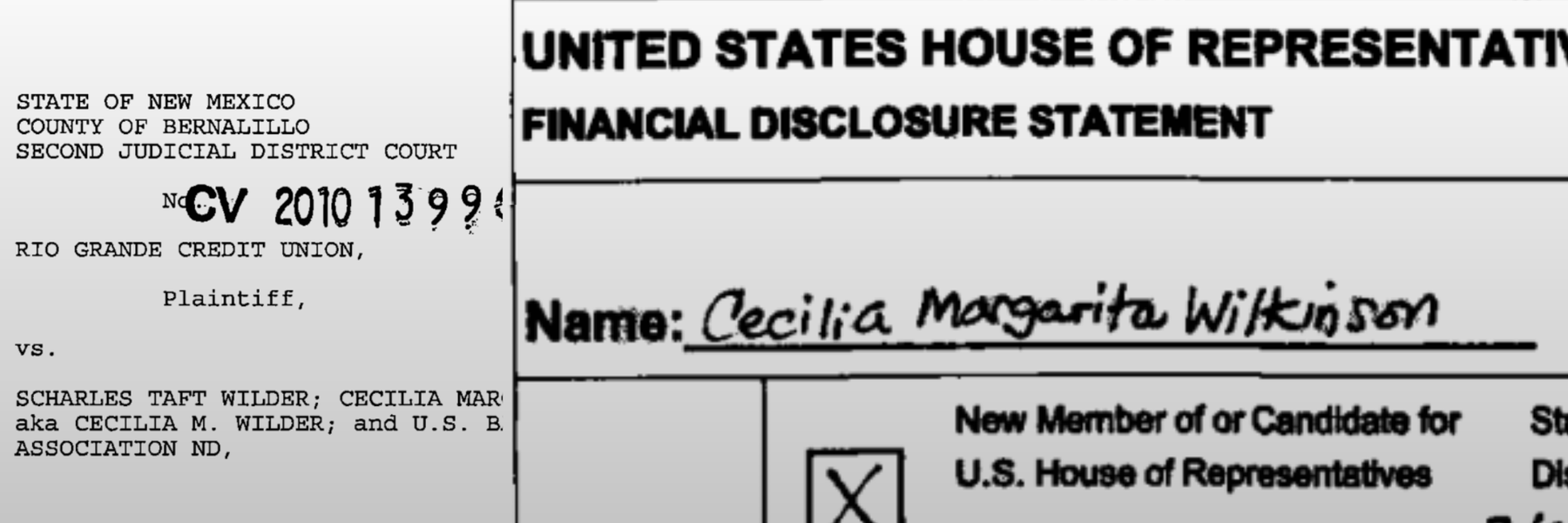

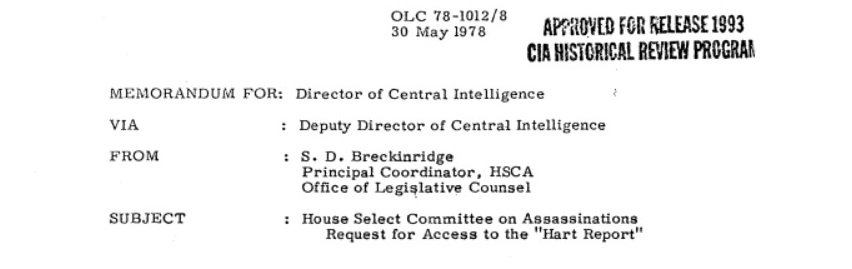

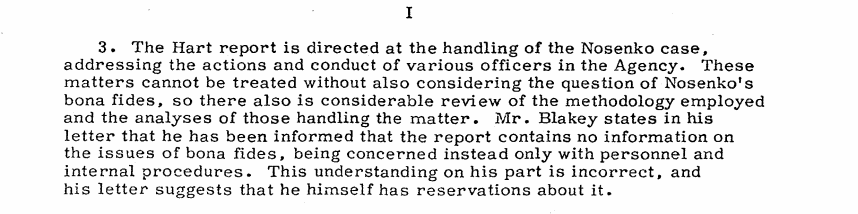

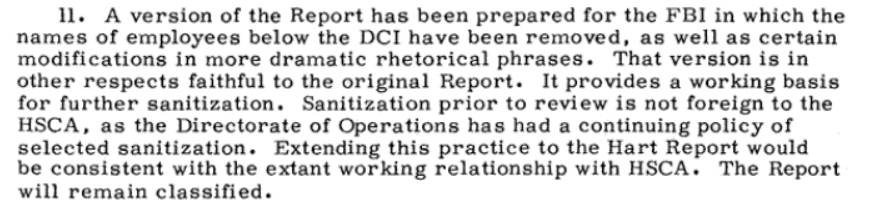

After Director William Colby forced Angleton out of the Agency and the Family Jewels exposed some of what had been done to Nosenko, another report (at least the third) examining the Nosenko case was ordered. The report made by CIA officer John Hart, who admitted to exceeding the original scope of the report. What he produced was a report that Angleton alleged was libelous, a concern that seems to have been shared by Hart and the CIA. When it came time to share the report with the FBI, the Agency did more than simply sanitize it of references to specific individuals. As MuckRock previously reported, the Agency made “certain modifications in more dramatic rhetorical phrases.” When the report was requested by the House Select Committee on Assassinations, CIA gave them the rewritten version of the report after removing an additional chapter.

When MuckRock first reported the modification Hart Report, the extent of those modifications were unknown. The HSCA version of the report has now been released. Where the original report was 202 pages long, the version the HSCA received was only 175 pages. A review of the sanitized report shows that far more than dramatic phrases were modified - an extensive amount of content was removed. Most egregiously, this version of the report made no mention of Oswald or the JFK assassination, while the original (still not available, despite having been requested over a year ago and ostensibly already being declassified) did.

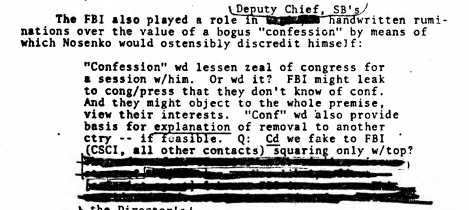

In other instances, it’s clear what the Agency’s claim that “dramatic, rhetorical phrases” was at least somewhat euphemistic for human rights abuses. While the original report has yet to be released, a copy of Hart’s notes do include passages removed from the HSCA version of the report. These notably include suggesting faking a confession from Nosenko in order to reduce the FBI’s interest in him.

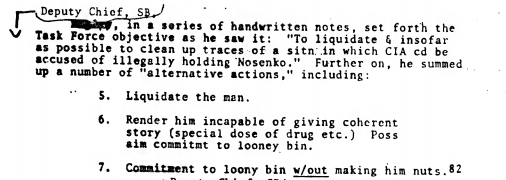

Another handwritten note listed liquidating Nosenko as a possibility, along with potentially drugging him so he could no longer give a coherent story, and/or having him committed to a mental institution. The author of the notes, Pete Bagley, later explained that these were not serious suggestions but merely part of a complete list of options open to the Agency - an explanation that provides most with little comfort.

In a “dramatic phrase” that spanned several pages, the Hart Report originally quoted a plan to kidnap and isolate Nosenko. The plan included placing him in a prison environment explicitly modeled after the KGB Lubyanka prison. Nosenko would spend years in isolation in a cell CIA had specially built for him on American soil. The plan, in an episode that would be referred to in the Senate torture report’s section on the history on CIA interrogation, is worth quoting in its entirety.

The operational and psychological assessments of Subject suggest strongly that the timing and the staging for the “arrest,” and the physical surroundings and psychological atmosphere of the detention could influence Subject strongly, and if properly done, could go a long way towards “setting him up” for the interrogators. For this reason, we wish to emphasize that apart from the purely mechanical problems involved, every member of the guard force will have an important part to play as an actor.

Briefly, the plot is as follows: On the evening of April 2 (the actual date may yet be moved up or delayed a few days), a team of four or five security officers will pull up to the present safehouse in a van or panel truck. Three of them, all unknown to Subject, will enter the safehouse, will inform Subject that he is under arrest, slap handcuffs on him, lead him out to the van and hustle him into the rear of it. All of this is to be done as quickly as possible, and with an absolute minimum of conversation.

Subject is not to be allowed to take anything with him, and any questions or requests on his part are to be completely ignored. It is anticipated that he will put up physical resistance and, if necessary, the security guards already at the house can bear a hand;

However, if possible it would be desirable that they stand completely apart. What we are after in this initial scene is complete surprise, and also to keep Subject in suspense for as long as possible as to who is perpetrating this outrage on him and why. Therefore, it would be desirable for the new ’’hostile guards” and the old ’’friendly guards” at the safehouse not to let on that they know each other. The van will then proceed to the Detention House. Subject will remain handcuffed throughout; seated in the rear of the van with three guards he should be unable to see anything of the route. The guards should continue to ignore anything he may say; nor should they speak to each other –an atmosphere of stony and even unnatural silence is just what we want.

Upon arrival at the Detention House, Subject is to strip completely and to put on prison attire. Again for psychological reasons, it would be desirable to have genuine prison clothes; failing that, coveralls and slippers without laces, or something along those lines will do. The senior officer at the Detention House should play the part of “warden.” He is the one who should explain the “prison rules” to Subject and “assign him to his cell.” For a cell, Subject should have the smallest room in the house. From the description, one of the attic bedrooms sounds about right. It is to be furnished with a cot, a hard chair and a slop pail. Nothing else.

The window will be grilled, and there should be a single overhead light bulb (about 60 watts) for illumination. This light will remain on at all times. There should be a screened observation window in the cell door, and Subject is to be under observation at all times that he is in the cell. There is no need for this to be covert; in fact, we want Subject to feel that he is under a microscope. Under no circumstances should the guard talk to Subject, however. The prison routine is to be patterned after the description provided by Prof. Barghoorn of his stay in the KGB prison in Lubyanka. Subject will be made to rise at 0600. He will then be taken to the WC where he will be allowed to empty his slop pail and wash up (cold water only).

Particularly at first we want to keep him as much in the dark as possible as to what went wrong, who are the new people who arrested him, where was he taken, and above all, what is in store for him. In the Detention House, we want to create an atmosphere in which he feels totally cut off from the world, trapped in a situation from which there is no escape, caught in a dismal trap in which he may be stuck for the rest of his life. To this end, we would like for him not even to hear the sound of human speech any more than is absolutely necessary. The section of the house in which the cell is located should be sufficiently well shielded acoustically from the rest of the house so that Subject cannot hear the sounds of voices, laughter, telephone calls, comings and goings, etc.

No one should ever so much as smile in his presence. No one except the interrogators should ever talk to him.

The decision to provide the HSCA with a version of the Hart Report that had been modified to leave these portions out is somewhat confounding given their inclusion in Hart’s presentation before the HSCA. Several of these things, however, were to have been left out of the presentation as well. A CIA memo describing his presentation states that he went off script in including it after agreeing not to.

In addition to omitting dramatic phrases and human rights abuses, the Agency explicitly planned for Hart to not discuss Nosenko’s comments on Oswald with the HSCA.

The Agency’s handling of the HSCA report, and rewriting it to omit the CIA’s abuses (whether actual or contemplated) raises significant questions about their transparency with Congress and their ability to address their moral and legal shortcomings. MuckRock has filed a new FOIA request to learn more about the modifications to the report, and the next part in this series will explore the report’s contents. In the meantime, you can read Hart’s notes and a selection of relevant memos below.

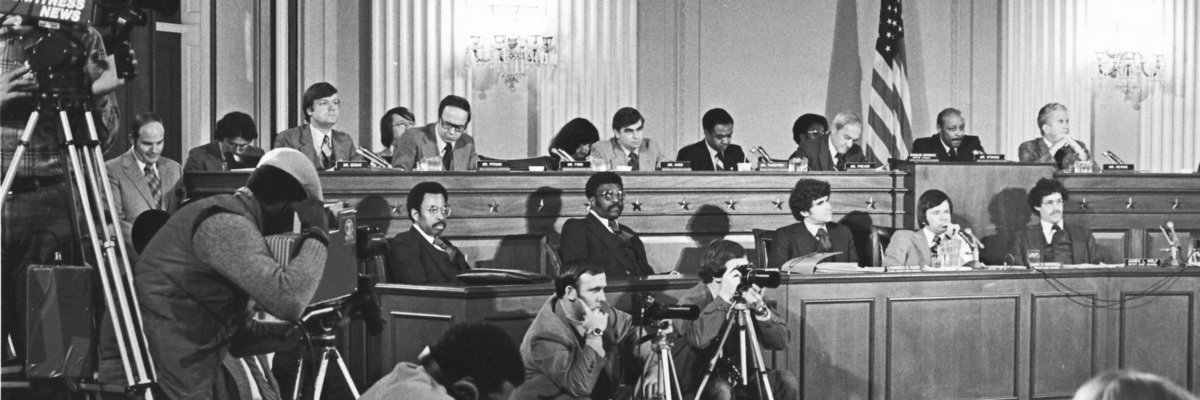

Image via Office of the House Historian