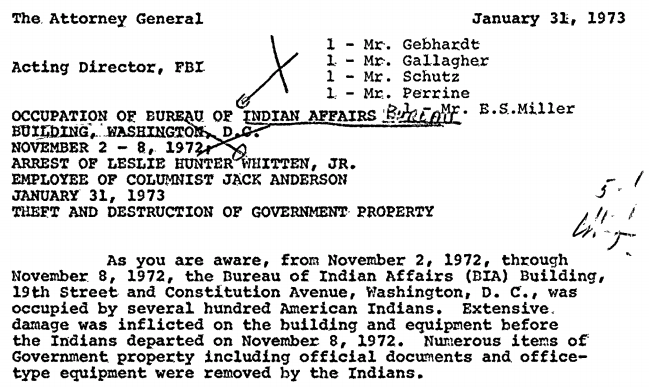

The occupation of the Bureau of Indian Affairs building by the American Indian Movement resulted in lost and damaged property, and a number of documents being stolen from the building. The Federal Bureau of Investigation investigated some of these thefts, including an alleged plot by journalists Jack Anderson and Les Whitten to pay for these records. The FBI file on the affair describes how a retired Justice Department senior official contacted the Bureau’s current staff to vouch for Whitten, referencing his history of cooperating with the FBI as a confidential informant.

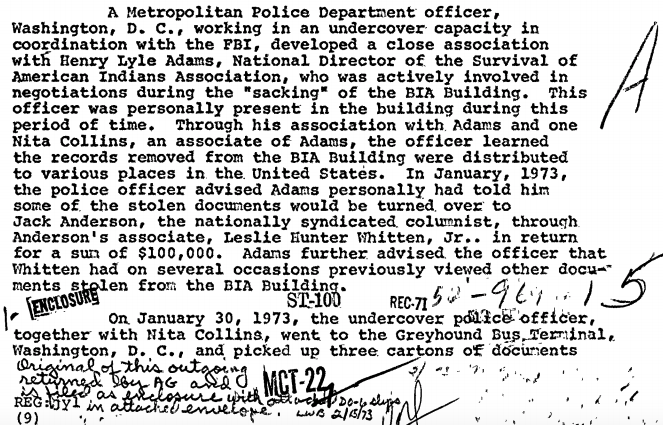

According to the files, a Metropolitan Police Department officer working undercover in Washington D.C. developed a relationship with the National Director of the Survival of American Indians Association, Henry Adams. The undercover officer reportedly learned from Adams that stolen BIA documents were being distributed around the United States. Several months after the building’s occupation and “sacking,” the officer was allegedly informed that Anderson was going to buy some of the stolen documents for either $100,000 or $200,000 through Whitten, an associate of Anderson’s. The officer was with Anita Collins, news editor for the AIM when they went to retrieve the documents for Whitten.

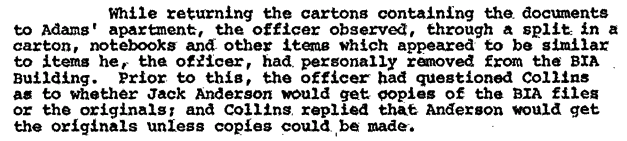

The two took the documents to Adams’ residence, where Adams said they were going to go through the documents to decide what to give to Anderson and Whitten. The undercover officer reportedly recognized some of the materials as very similar to ones he had personally removed from the BIA Building in his capacity as an undercover officer. The officer asked Adams what would later be a key question for the investigation - were they going to give Anderson the original documents, or copies? Adams reportedly answered that they would give Anderson the originals, ‘unless copies could be made.’

Once these facts were established and relayed to the FBI, the Bureau sought and received approval from Assistant U.S. Attorney William Collins (no relation to Nita Collins), to arrest those involved with the documents and seize the relevant evidence. On the morning of January 31st, 1973, FBI officials watched as Adams and Whitten met outside of Adams’ residence. They were arrested and three cartons of materials taken from “the November siege of the BIA Building” were seized as evidence.

The Bureau noted that Anita Collins had reportedly planned to claim they intended to return the materials to the FBI in the event they were caught, according to the undercover officer. The cartons were marked in a way consistent with this, as the Bureau noted. Whitten reportedly claimed the FBI would make this information disappear.

The officer requested permission to wear a wire to record these conversations, though the files released so far don’t clarify whether or not it was granted. It is worth noting, however, that the Bureau seemed to plan on relying on the officer’s testimony, rather than recorded conversations.

Anderson presented the same version of events that Whitten did. In one phone call to Special Agent Hyten, Anderson rather politely threatened the man with his journalistic chops.

Adams’ version of events also conformed with Whitten’s, adding that he had previously returned some of the information to Hyten at the FBI. Hyten acknowledged receiving one envelope from Adams following the siege, containing what the FBI’s file described as “fragmentary bits and pieces of brown paper which were generally illegible.” There was no note of explaining, leading Hyten to conclude “they were not pertinent.”

The FBI was apparently able to reconstruct more of the files’ travels than Whitten expected, identifying the busbill, the place of origin and the person who picked up the packages..

In contrast the undercover officers’ statements about returning the documents having been a cover explanation, several pieces of evidence do offer some support for the innocent explanation. In one instance, the Acting Director of Communications for BIA had received word that Adams and Whitten believed the documents would be returned to BIA by February, a timeline consistent with Adams and Whitten’ arrest date. According to FBI interviews with BIA personnel, no specific arrangements were made, however.

Others, however, were less consistent with the denials. Anita Collins, for instance, pleaded ignorance. She knew of the cartons, but not their contents. She was present for the occupation, but neither took any documents nor knew of anyone who had. She had been there to help negotiate in a meeting and in her capacity as news editor for AIM. The occupation hadn’t been planned by her or any of the others present for it.

A key point of the investigation was determining the monetary value of the documents. The two sums that Anderson and Whitten had reportedly been willing to pay for it provided an upper bound of $100,000 and $200,000 (just under $600,000 and $1,200,000 in 2018 after adjusting for inflation). The BIA had trouble establishing a “recovery value,” which only had to be $100 or more for the matter to be a felony.

The Bureau eventually determined that the cost of the papers and binders themselves “would be valued at approximately $100.” According to the FBI’s file, the approximate cost could be as high as $100 per page “if binding, preparation, distribution, and other administrative handling of same was considered.” The threshold for a felony was easily exceeded, according to the FBI’s understanding. If they had been copied instead of stolen, the government’s case likely wouldn’t have existed.

The matter seemed relatively straightforward - it would boil down to Adams and Whitten’s word against the MPD officers’ and FBI personnel involved. With the MPD and FBI extensive paper trail, it likely seemed easy to build a case more convincing than Adams’ illegible bits of paper and Whitten’s claims. However, the matter became more complicated when former FBI Assistant Director Robert Wick called the FBI to give them context about Whitten.

According to Wick, Whitten was honorable and “completely honest.” Moreover, Whitten had worked as an informant for the Bureau. According to Wick, “Whitten in the past furnished information to the FBI and was of great assistance in utilization of information.” Moreover, Wick believed Whitten was the one directing Anderson, rather than the other way around.

Wick had spoken with Whitten about the matter, and believed he was telling the truth about his intention to return the documents. Whitten admitted that his interest wasn’t purely selfless, however. He was going to provide transportation for the documents, but would “look at the documents for a scoop before they were returned.”

The FBI noted that, contrary to Adams and Whitten’s claims, it was not necessary for Whitten to transport the documents if the intent had been to return them. The Bureau specifically pointed to the use of the MPD officer and their transportation to retrieve the documents, as well as their availability on the day in question, as evidence that that Whitten “was not essential for transportation purposes.”

The resolution of the case isn’t described in the documents released so far, though it may have involved a retaliatory leak that was used as insurance for Whitten. MuckRock has filed several new FOIAs to obtain more documents on this and related matters. In the meantime, you can read the first 235 pages below, including a transcript of Anderson’s and Whitten’s version of events.

Image via Wikimedia Commons