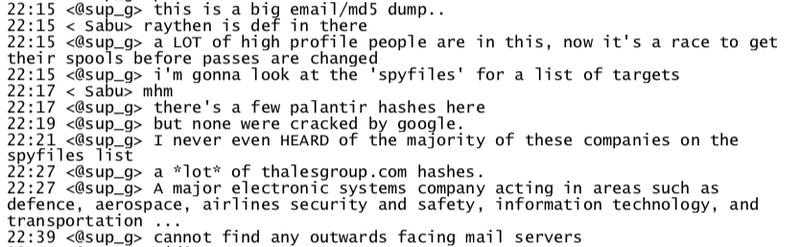

Documents from a leaked FBI file reveal more of the symbiotic relationship between WikiLeaks and the hackers that supplied the organization with the Stratfor emails and the Syria files, two of the organization’s largest and most significant publications. A week after the organization gave the hackers special access to an email search engine, the hackers were using the search engine to identify additional targets to hack. According to the chat logs obtained by the FBI, the hit list of surveillance companies resulted in at least one successful breach, casting further doubt about the organization’s publication model and its relationship with various hackers who’ve numbered among its sources.

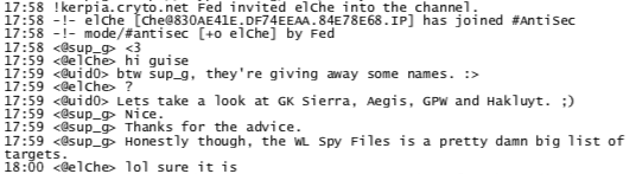

The chat logs from the FBI’s file show that the idea to mine the WikiLeaks’ database for targets occurred to the AntiSec hackers early on. In one late December 2011 exchange in #antisec, one user suggests a possible list of targets to sup_g, one of several aliases of and the then-current handle of Jeremy Hammond. In response, Hammond politely declined using the list. “the [WikiLeaks] Spy Files is a pretty damn big list of targets.”

By January 1st, chat logs indicate that Hammond had moved from prospective use of the Spy Files as a target list to active exploitation. This decision appears to have been simultaneous and complementary to the group’s exploitation of the Stratfor emails and user database. There is no mention of whether using the Spy Files as a target list had been suggested to Hammond, though the idea to use it as such came after the group had been asked to hack Icelandic targets on behalf of WikiLeaks, a case that the organization appears to have believed was being developed against them and which would form a cornerstone of the FBI’s files on the organization. Hammond’s use of the Spy Files also came after WikiLeaks gave the hackers special access to tools to help them exploit the Stratfor files, as revealed by Gizmodo.

In the January 1st chat log, a redacted version of which was previously published by Dell Cameron, shows that Hammond had been actively reviewing the Spy Files “for a list of targets.” According to the chat log, in-between comments about exploiting the Stratfor breach, Hammond stated that he had “never even heard of the majority of these companies on the spyfiles list.”

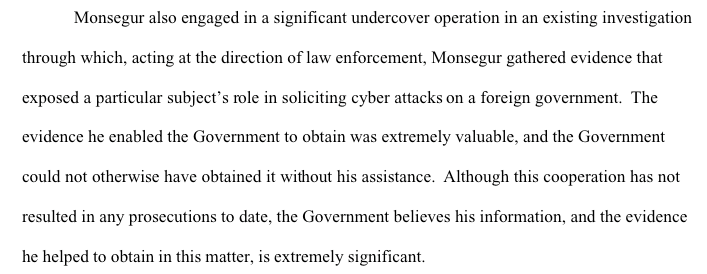

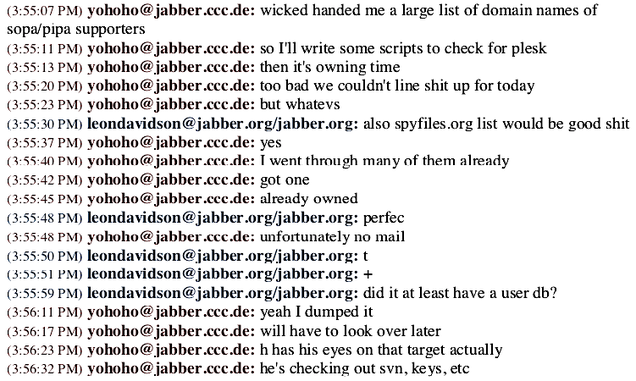

Two weeks later, the exploitation of the Spy Files was well underway. In mid-January, the exploitation was suggested by Hector Monsegur, who was then acting as an informant for the FBI known online as Sabu. According to the chat log, Monsegur said that the list “would be good shit.” Hammond agreed, and revealed that he had already gone through “many of them.” One of them, Hammond said, had already been breached. He had been unable to take any of the company’s emails, but he had snagged their user database, which they planned to further exploit. Another member of the group had their eye on the company, with the goal of putting a backdoor in the software the company sold.

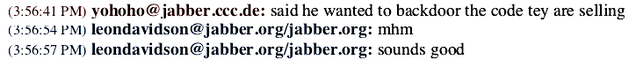

The next page of the logs shows that another member of the group had their eye on the company, with the goal of putting a backdoor in the software they sold.

The following year the organization released a supplement to the Spy Files. According to the organization’s statement at the time, “WikiLeaks’ Counter Intelligence Unit has been tracking the trackers.” As part of the release, WikiLeaks’ Counter Intelligence Unit (WLCIU) produced a list of what it called “ALL Targets” from 2011-2013, listing security and surveillance companies, the names of their employees and the employees’ locations at different times.

Although the FBI’s files documents the hackers’ exploitation of WikiLeaks’ Spy Files and the symbiotic relationship the transparency organization had with the hackers, it’s unknown if alleged charges against the organization’s founder, Julian Assange, relate to this.

On January 23rd, WikiLeaks announced its intention to “force” the Department of Justice to unseal charges against Assange as part of “a comprehensive 1,172-page application.” Previous efforts to unseal charges against Assange have not been able to receive official confirmation that charges against the WikiLeaks founder currently exist. According to the organization, the application “reveals” that “U.S. federal prosecutors have in the last few months formally approached people in the United States, Germany and Iceland and pressed them to testify against Mr. Assange in return for immunity from prosecution.” To date, the organization has not cited evidence for this claim, which have been widely reported but entirely unverified. As WikiLeaks revealed who was allegedly approached, it’s unknown if they’re connected to any of the hacking cases surrounding the organization.